In Studies of the Histories of the Renaissance, Walter Pater (1839-1894) situates the origins of that “many sided but yet united movement” known as the Renaissance in 13th century France. Like many a universalizing concept, the “Renaissance” originally referred to a specific cultural and historical era “in which the love of the things of the intellect and the imagination for their own sake” flourished and thus engendered the movement which bears its name. “Of this feeling,” where the imagination and intellect both opened to the revival “of old and forgotten sources” from the classical world, Pater cites “a great outbreak” at the end of the mediaeval period. From Gothic architecture to “the doctrines of romantic love, in the poetry of Provence, the rude strength of the middle age turns to sweetness, and the taste for sweetness generated there becomes the seed of the classical revival in it.”

Dante and Boccaccio are the two great writers of the late Middle Ages generally credited with heralding the “classical revival” in 15th century Italy that would define the start of the modern western world. Pater takes one step further back to consider “this notion of a Renaissance within the limits of the middle age itself.” French seeds enabled “the magnificent aftergrowth of that poetry in Italy,” and across Europe.

The troubadours were the “inventors of romantic love” in that theirs were among the first notated love songs. If their subjects did not always predict the Renaissance obsession with the Hellenic world of Greece (and Rome), their themes were parallel with those of Homer, Virgil and Ovid. Songs of the bards revolve around heroism and love, conquest and defeat, the sweet spoils of victory and the bitter tonics of loss. In the middle of that “dark age,” there arose “a world in which the world could be rewritten” in the remarkable marriage of poetry and song. Richard Zenith echoes Pater in calling troubadour poetry “another plane of reality… autonomous, transforming the first expressions of the unrelenting individuality that was to lead to the Renaissance.” (113 Galician – Portuguese Troubadour Poems. Carcanet, 1995.) If Homer was our prototypical bard, the original singer-songwriter, then the troubadours were the first “composers,” reviving the ancient tradition of storytelling through singing, then writing the songs down for others to “cover.”

If the troubadours were motivated to find escape and release from the hardships of the “mean life” of their “dark age,” they ”transferred the feudal concept” of the secular plane and merged it with “the Christian idealization of Mary.” In other words, the troubadours united sacred and profane love. This mystical and sensual syncretism would fuel not only the Renaissance movement but find another creative resurgence in the 19th century Romantic period. In addition to renewed interest in the classical world, these vibrant artistic periods were marked by an interest in the ancient sagas of Northern Europe, from Celtic and Druidic legends to the Nibelungenlied of Germany and the Icelandic Eddas. Do I hear an opera?

Another syncretist aspect of the troubadour tradition was the hybrid nature of its form. As Venice would be a cross-cultural center merging Christian, Jewish and Islamic traditions of music and art in the Renaissance, the songs of the troubadours blended European, Hebraic and Arabic elements nearly a millennium before “globalization” came into vogue.

“In that poetry,” Pater writes of the troubadours, “earthly passion, in its intimacy, its freedom, its variety – the liberty of the heart – makes itself felt.” The apparent timelessness of these sentiments is one of its essential and universalizing qualities. Before turning to the Provencal poem that is his introductory chapter’s subject, Pater reminds his readers of the “the great lover,” Abelard, who “connects the expression of this liberty of heart with the free play of human intelligence round all subjects presented to it.” The object of Abelard’s love was the classical scholar (his former pupil), Héloise. Her education was “then unrivalled,” thus “enabling her to penetrate into the mysteries of the older world…like the Celtic druidesses.” Alexander Pope, in his famous 1717 Ovidian epic poem, based on letters discovered from their illicit 13th century affair, echoes this connection to the “mysteries.”

How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot.

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!

Each pray'r accepted, and each wish resign'd.

The third line of that verse (the 209th in the poem) became the title of a Charlie Kaufman film. The equally cryptic and delightfully wry Being John Malkovich, another cult favorite Kaufman film, features an “Eloise and Abelard” puppet show. The poem is the inspiration for an evocative soprano aria by our esteemed friend, the composer Deborah Mason. It can be heard in a performance by Amy Cofield Williamson, who recently recorded “Eloise to Abelard” to help promote Mason’s Alexander Pope – inspired opera, The Rape of the Lock. One never knows what surprises are in store within the labyrinth. The joy of discovery is its own reward.

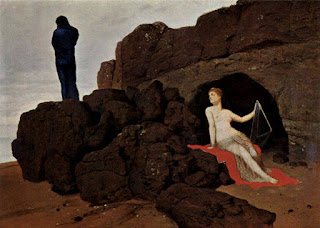

(Leighton's 19th century canvas, "Eloise and Abelard")

Punished by provincial relatives for defying convention, “Abelard became a monk and Héloise a nun.” As referenced above, “their relationship survived in the form of their correspondence.” Is it any surprise the mother of all muses is Mnemosyne or Memory? It has been said the most important word in Judaism, as vital as it is simple, is: “remember.” That is the best answer I know to the not infrequently asked question, “why do you spend so much time with the past?” Anyone who has lived in the company of those whose memories are suspect – whether from laziness or disingenuousness – knows the ever-present truth of another famous maxim. “Those who forget the past are doomed to repeat its mistakes.” These musings are affirmative efforts, modest attempts to illuminate corners of the past often hidden in shadows. They aim to be re-creations of neglected stories, encores of forgotten songs, re-minders, re-discoveries and re-connections.

In an endnote to the Oxford paperback edition of Studies in the History of the Renaissance, Matthew Beaumont includes a paragraph Pater added to subsequent editions of his classic study.

The opposition into which Abelard is thrown…which breaks his soul to pieces, is a no less subtle opposition than that between the merely professional, official, hireling ministers of that system, with their ignorant worship of system for its own sake, and the true child of light, the humanist, with reason and heart and sense quick, while theirs were almost dead. He reaches out towards, he attains, modes of ideal living, beyond the prescribed limits of that system… As always happens, the adherents of the poorer and narrower culture had no sympathy with, because no understanding of, a culture richer and more ample than their own.

“Holy indictment, Batman! Have artists always railed against the corrupt and philistine world and been suspicious of systems and institutions?” Yes, Robin. That is one of the reasons why the mother of muses is named Memory, and not Profit, Expedience, or Status Quo. Though we trouble-making complainers have always been in the minority, we have always been, and our songs have always taken up the themes of opposition. When Pater writes of “the poorer and narrower culture” he is not describing an impoverished or “primitive” society but a culture of the creative mind. The “poorest” village may very well have the richest of cultures. “One of the strongest characteristics of that outbreak of the reason and the imagination, of that assertion of the liberty of the heart in the middle age, which I have termed a mediaeval Renaissance, was its antinomianism, its spirit of rebellion and revolt against the moral and religious ideas of the age.” He means the repressive moralism that contributed to the age’s description as “dark,” lest this aesthete be dismissed as immoral, amoral or degenerate. That Pater was gay in a time when it was even more dangerous to be “out” contributed to his neglect. He describes a “return of that ancient Venus… those old pagan gods still going to and fro on the earth, under all sorts of disguises. The perfection of culture is not rebellion but peace; only when it has realized a deep moral stillness has it really reached its end.” And artists have used all sorts of tricks to rejuvenate those gods and precipitate that utopian perfection of culture through the synthesis of art and science, the marriage of sacred and profane love, and the union of harmonious social ends through cultural means.

A favorite “trick” of the Romantics was to “rediscover” or “translate” or simply “adopt” the persona of an ancient. Just as the mad poet Artaud would take on his crazy great uncle Nerval’s mantle in the 20th century, the Romantic Scots poet James MacPherson “became” the ancient Gaelic bard, Ossian. An inspiration to Goethe and Schubert and beloved by Thomas Jefferson, “Ossian” was a 19th century re-creation of one of the ancient Homeric or Ovidian or Druidic bards – to quibble over the semantics of his “authentic” origins is to miss the romantic point entirely. While it does matter when and where the “Arabian Nights” originated, such factual debates can overshadow the symbolic relevance of its contents and its essential contribution to our understanding of the mythologies of ancient Africa and Arabia. Like the troubadours, Ossian sang “some intenser sentiment,” which came “from the profound and energetic spirit” of “poetry itself.” Regardless of either’s “origins.”

(Girodet's early Romantic canvas, "Ossian receiving the Ghosts of Fallen French Heroes"

Ossian thus serves a parallel function to the Valkyries of Norse legend and Wagner...)

Pater’s allusion to “that ancient Venus” is a reference to the legend of the German Minnesinger (or troubadour), Tannhäuser, the subject of Wagner’s most autobiographical opera. As was his wont, Wagner conflates his ancient sources with original inspiration. He marries the legend of the 13th century troubadour consort of Venus with the famous “singing contest” at Wartburg. The novel in which Novalis develops his romantic archetype of longing in the symbol of the “blue flower” is Heinrich von Ofterdingen. Heinrich is one of the singers of the Wartburg Sängerkrieg, and in Wagner’s opera, he is Tannhäuser. The other Minnesingers (or Knights and Minstrels), like Walther von Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach were historical figures. Wagner read plays and poems from several authors, such as Tieck, Hoffmann, Heine and Eichendorff. He then united aspects of the historical singing contest with the legend of the (historical) crusading knight who spent seven years in Venusberg with the goddess of love, in a crusade of an entirely different order.

Tannhäuser is not only the ultimate operatic treatment of the conflict between sacred and profane love, it is one of the great music dramas of the artist’s complex relationship to society. As a romantic “renaissance” of classical characters and settings, it is a 19th century portal to the ancient world and a window into the soul of its creator. It is all of these at once. Let’s consider one detail. Venusberg is a cave or grotto. Though Wagner does not mention Novalis, the grotto is the setting of the archetypal blue flower, and Novalis’s description of the scene is worthy of a Wagnerian treatment. Here is John Owen’s translation (from Project Gutenberg):

On entering this expanse, he beheld a mighty beam of light, which, like the stream from a fountain, rose to the overhanging clouds, and spread out into innumerable sparks, which gathered themselves below into a great basin. The beam shone like burnished gold; not the least noise was audible; a holy silence reigned around the splendid spectacle. He approached the basin, which trembled and undulated with ever-varying colors. The sides of the cave were coated with the golden liquid, which was cool to the touch, and which cast from the walls a weak, blue light. He dipped his hand in the basin, and bedewed his lips. He felt as if a spiritual breath had pierced through him, and he was sensibly strengthened and refreshed. A resistless desire to bathe himself made him undress and step into the basin. Then a cloud tinged with the glow of evening appeared to surround him; feelings as from Heaven flowed into his soul; thoughts innumerable and full of rapture strove to mingle together within him; new imaginings, such as never before had struck his fancy, arose before him, which, flowing into each other, became visible beings about him. Each wave of the lovely element pressed to him like a soft bosom. The flood seemed like a solution of the elements of beauty, which constantly became embodied in the forms of charming maidens around him. Intoxicated with rapture, yet conscious of every impression, he swam gently down the glittering stream.

Novalis could be describing Wagner’s Venusberg or Homer’s Ogygia, where Odysseus spends seven years in exile as the consort of the immortal nymph, Calypso. Hard labor, as it were. The parallel with Tannhäuser would not have been lost on the romantics. Nor is it coincidence that Wagner’s Dutchman is cursed to sail the seas for seven-year periods. The love he tried to portray in the opera he wrote immediately after Der Fliegende Holländer continues its main theme. Tannhäuser is also “about” the search for ideal love. Barry Millington (quoting Wagner in Wagner. Princeton, 1984) notes he “was longing ‘to find satisfaction in some more elevated and noble element which…I conceived as being something pure, chaste… inaccessibly and unfathomably loving.’” His wish “to perish in that element of infinite love which was unknown on earth” aligns the Dutchman and Tannhäuser with the leitmotif of his life. It is the redeeming “love-death,” the Liebestod so famously represented in the apotheoses of Tristan & Isolde and Götterdämmerung.

(Böcklin's expressionist canvas of "Odysseus and Calypso," from the year of Wagner's death, 1883)

Baudelaire was so transfixed by the 1860 performance of Tannhäuser in Paris he was compelled to write to the composer to express his admiration using “a comparison borrowed from painting.” He continues, “I imagine a vast expanse of red spreading before my eyes. If this red represents passion, I see it change gradually… until it reaches the incandescence of a furnace. It would seem difficult, even impossible, to render something more intensely hot, and yet a final flash traces a whiter furrow on the white that provides its background. That, if you will, is the final cry of a soul that has soared to a paroxysm of ecstasy.” (from Musica Ficta: Figures of Wagner, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, translated by Felicia McCarren. Stanford, 1991).

“No one writes with abandon anymore,” Verdi complained just a few years after Baudelaire articulated his soul’s wild flight to the most ecstatic composer the world has known.

Wagner’s “love-death” is the redemption of the individual and ultimately, the world. It is the homecoming from exile, the return at the end of a journey, the reaping of the harvest after the due season of sowing. The “mysteries” of the ancient world and the periods of renaissance where interest in them has revived share this cycle.

In his tales of the Valois, where “for more than a thousand years the heart of France has beaten,” Wagner’s first French-poet-disciple, Gérard de Nerval recalled the ancient world and alluded to the mysteries (Selected Writings, trans. R. Sieburth. Penguin). “I have passed through every circle and trial of those scenes of ordeal commonly called theatres. ‘I have eaten of the drum and drunk of the cymbal,’ as the apparently meaningless phrase of the initiates of Eleusis runs. It no doubt means that, if need be, one must pass beyond the bounds of nonsense and absurdity…”

By sharing his interpretation of the “apparently meaningless phrase,” Nerval is letting us in on the fact these mysteries and their cryptic rituals and songs actually do mean something. Those Eleusinian initiates were participants in an ancient rite that symbolized the journey of life itself. Departure. Journey. Return. (Repeat.)

It may be absurd to spend one’s life writing or composing or singing about cursed captains and lovesick troubadours and troubled souls and the ken of their kin. As a colleague reminded me just yesterday, “earth” without art is just “eh...”

No comments:

Post a Comment